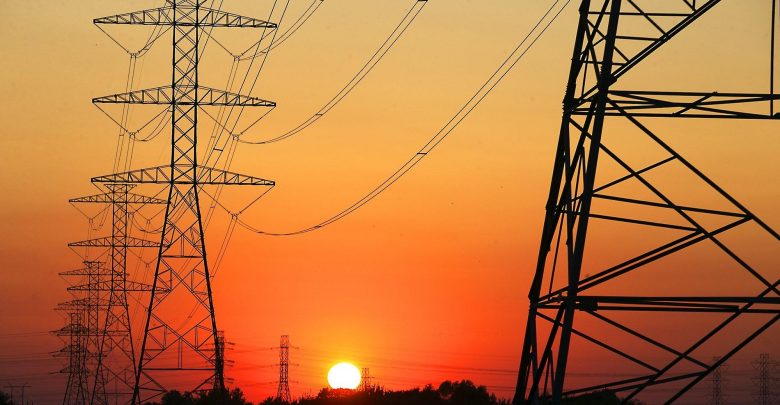

Zim power crisis has no short term solution

Zimbabwe will continue to struggle to stabilise power supply in the short term as the water level at its biggest source of electricity, Kariba South Power Station, continues to decline following the poor rains received around the reservoir’s catchment area.

Lake Kariba, from where Kariba South hydro power station draws water to produce electricity, has seen a weighty 41 percent reduction in live water (water available for power generation), from the already low live water holdings the same held last year the same time, which stood at 46 percent.

In fact, the biggest challenge facing Zimbabwe at a time the hydro power station is facing power generation constraints due to the extremely low water levels in the lake is that Kariba South is being used as a baseload (regular supply) power station.

This also comes as Hwange Power Station, Zimbabwe’s second largest and supposedly baseload power plant with a rated capacity of 920 megawatts, is currently able to generate an average of 500MW due to aged equipment.

The thermal power plant was built in the mid 80s and has outlived its economic life.

While a similar capacity expansion programme to the one completed at Kariba South in April 2018, adding 300MW, will have the first of its two by 300MW generators coming on line by November this year, the second is only expected in the first quarter of next year.

In between, Zimbabwe will have to continue to rely on the curtailed output at Kariba and reduced and unreliable supply from Hwange (which does not come into full operation until at least March next year) as well as imports from the region.

Acute coal shortages, despite huge deposits of the fossil fuel in the country, grounded the country’s thermal power stations for 142 days during the first quarter of this year, triggering a sharp fall in production, the Zimbabwe Power Company said.

This means the country might not see significant output increase from its new thermal capacity if the coal producers, concentrated in Zimbabwe’s Matabeleland North region, continue to struggle operationally due to unviable domestic coal prices.

With Kariba generating at significantly reduced capacity and the Southern Africa country continuing to face challenges accessing foreign currency to import power from the region, Zimbabwe looks a long shot away from power security.

Demand for power in Zimbabwe currently exceeds 2 800MW while the country can only afford average domestic production of 1 400MW, which forces state power utility Zesa Holdings to implement long hours of load shedding to balance up demand and supply.

This significantly affects industrial, commercial and household activity. Recently, the State power utility entered an agreement with exporters to charge them in forex to raise the funding required to import power, but even then, there are no guarantees for uninterrupted supply.

The lake level at Kariba South, a 1050 megawatt power plant, has been decreasing steadily on account of low inflows from the mainstream Zambezi River, closing the period under review at 479,34m (27,02 percent usable storage) on 16th August 2022, compared to 481,88m (46 percent usable storage) recorded on the same date last year.

Lake Kariba is designed to operate between levels 475,50m and 488,50m (with 0,70m freeboard) for hydropower generation. The hydrological system that feeds the Zambezi River, coupled to it Lake Kariba, means the reservoir may not have enough water for power generation until the end of the first quarter of next year.

En-route to the Indian Ocean, the Zambezi flows through a grand total of six countries; Zambia, Angola, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique. It spends the most amount of time in Zambia, and the least in Botswana.

The Zambezi River originates in the Mwinilunga District in north-west Zambia, 1500m above sea level. More specifically, the source is a marshy black wetland, known as a dambo, in the centre of the iconic Miombo Woodlands.

The Zambezi rises out of a marshy bog near Kalene Hill, Zambia, about 4 800 feet (1 460 metres) above sea level, and flows some 20 miles before entering Angola, through which it runs for more than 175 miles.

In this first section of its course, the river is met by more than a dozen tributaries of varying sizes. Shortly after reentering Zambia, the river flows over the Chavuma Falls and enters a broad region of hummocky, sand-covered floodplains, the largest of which is the Barotse, or Zambezi, plain.

It is only after the Barotse Or Zambezi plains have been flooded that the floodplain releases much of its excess water into the Zambezi River at the peak of the rain season in January and February, does Lake Kariba receive its highest inflows around April/June.

Although the rainy seasons have improved over the last two years, droughts or erratic rainfall in the last couple years left the lake extremely depleted and struggling to maintain high levels of power output consistent with the hydro plant’s rated capacity.

Secretary for Energy and Power Development Engineer Gloria Magombo said despite the low water level, Kariba had been able to supply about 850MW consistently, although this sees Zesa run it on “barring” or curtailed mode during off-peak periods to conserve water.

During the period January to date, the Zimbabwe Power Company, a unit of Zesa, was allocated 22,5 billion cubic metres by the Zambezi River Authority (ZRA), which regulates the affairs of the Zambezi River and the lake on behalf of Zambia and Zimbabwe, for power generation and this translates to 5 312GWh and an average capacity of 606MW.

ZPC said that the lake level increased from 478,81m at the beginning of the quarter to a maximum of 480,21 on 14th June then dropped to 479,64m at the beginning of August 2022.

“This represents a 1,34m rise in lake level over the quarter. As at the end of Q2 2022, the station had consumed 13,59Bm3 against a revised target of 13,00Bm3.” The water rations are a tiny fraction of the amounts required for Zimbabwe and Zambia, which generates power on the northern bank of Kariba, to run the power stations consistently at full throttle.

“We have an additional 100MW we are getting now from Zambia. From Mozambique we get 100MW, 50MW from HCB and 50MW from EDM, which is a (total) of 100MW,” Eng Magombo said.

“They (regional suppliers) have not stopped supplying us, we have just been asking them (to give us more), but you know there also is a general regional shortage, as you know South Africa has their own problems,” Eng Magombo said.

She added that there was a non-firm arrangement for the supply of upto 400MW from South Africa. On the firm side, Eng Magombo said South Africa’s power utility Eskom was currently exporting about 100MW to Zimbabwe.

“So, if they are not load shedding we can up to 400MW. That is always there, but obviously, over the last couple of months they have also been struggling with their own supply,” she said.

“A 100MW from South Africa, 50MW from HCB, 50MW from EDM plus 100MW from Zambia; that’s about 400 additional megawatts which we are able to import, as firm capacity before we add what we can import if the suppliers are not under pressure.”

But the imports do not guarantee security of power supply given that Zimbabwe always struggled to pay due to challenges around securing adequate foreign currency to pay for the energy from the regional suppliers.

Zesa executive chairman Sydney Gata recently said “Zesa is under immense pressure to settle the ballooning power import debt.” He said the power utility “had secured an Afreximbank facility which it used to pay off the power import debt in February, but the debt is growing back exponentially, posing a threat on security of supply.”

Speaking to local media, Dr Gata said the South African power utility Eskom could sign longer deals with Zesco, which might keep Zimbabwe — already facing an additional 2 100 megawatt (MW) demand from mines and smelters — out of another supply deal with the Zambian power utility.

Former Zesa chief executive Engineer Ben Rafemoyo said Kariba South Power Station remained a key element of Zimbabwe’s energy mix, despite what he called temporary challenges posed by low water levels in Lake Kariba, given that it is easier and much cheaper to operate compared to thermal power plants.

“Kariba is very important; number one (because) it is renewable, number two it’s already existing, it’s something that we already have and to a large extent, other than the two units which we added two three years ago, it’s like we are milking a cow which is no longer demanding food, when you talk of units 1 to 6.

“Number three, hydro power stations, by their nature, are easily deployable. You can shut them down and bring them back into action a lot quicker. We are talking . . . within an hour you have your station up, if it had gone out because of a fault or system disturbance.

“You can bring the system into operation that fast, which you cannot do with a thermal power station, like Hwange thermal power, you take days and a lot of costs to bring back because you have to burn a lot of diesel to bring them back up to speed to produce electricity.

“So, in that respect, it is a very very good power station to have within your energy mix. The only challenge we have as a country is that we use it as a baseload power station. A baseload power station is the one which you run continuously until a machine has broken down or you have taken it out for maintenance,” he said.

Ordinarily, in instances where a country has a proper energy mix, Eng Rafemoyo said, hydro power stations are used to fill in the “toughs”), that is to bridge the supply gap that comes up as a result of sudden surge in demand, which exceeds the current supply because they are easily deployable and when the situation normalises, they are put on “barring” which is operating them at a significantly curtailed level.-ebusinessweekly