The Outside View: What is the inflation outlook? – Part 1

By The Woodpecker

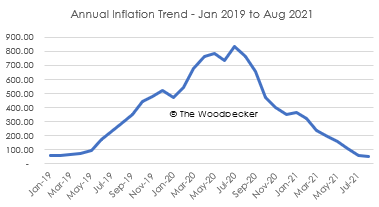

Both the fiscal and monetary authorities have repeatedly given assurances that the economic band-aid is firmly intact and effective, as evidenced by the twin surpluses – budget position and current account – exchange rate stability on the official foreign currency market, decelerating annual inflation – as shown in the graph – and upward revision in the 2021 GDP growth forecast to 7.8%, among others.

The authorities, in justifying recent decisions to stay the course on current policy interventions, further affirmed that the current positive trajectory is expected to persist into the near future, with a remarkable economic growth rate of 5.5% expected for the year 2022.

However, despite all these assurances, market players have continued to anxiously ask for independent opinions regarding the inflation, exchange rate, interest rates and economic growth outlook.

Such uneasiness is not surprising, though, given that results of the authorities’ policy interventions have mostly received backhanded compliments such as fragile stability, superficial surplus, and growth from a low base, among others, throughout the reform period.

Adding to the markets bewilderment is the authorities’ shifting targets, for example the several revisions to the expected 2021 year-end inflation rate from an initial projection of less than 10%, to a revised figure of less than 25% and now the recently revised range of 25-35%.

Furthermore, market jitters seem to have been worsened by the authorities’ seemingly heavy leaning on a foreign currency auction system, that, like its predecessor – which was introduced in January 2004 and later metamorphosised into a managed float system in April 2005 before being replaced by a Tradable Foreign Currency Balances System in October 2005 as relentless monetary expansion broke the camel’s back – is noticeably limping behind the alternative foreign currency market. Moreover, the auction market has noticeably continued to be sapped by the seemingly loose tightening of monetary policy and intermittent settlement backlogs.

Thus, given the importance of macroeconomic forecasts, especially as companies enter the traditional strategic planning period, I will, in this article, attempt to provide answers to some of the market concerns around the inflation outlook. However, this is not an easy task given the simmering radical uncertainty wherein the future is increasingly being determined by unquantifiable events, whereas market participants’ behaviours are mostly shaped by past events and memories. Worse still, the lack of up-to-date data on variables such as money supply growth – a key variable in forecasting inflation – makes it nearly impossible to build reliable mathematical models.

Thus, given that, under such circumstances, the use of traditional mathematical equations usually leads to precisely wrong conclusions, I will try to get it roughly correct by using a combination of past events, case studies, rules of thump and an open mind in building possible scenarios.

But, first, it is important to establish and understand the major drivers of inflation, and the attendant shock absorbers, in Zimbabwe. In fact, since the macroeconomic reforms that began in 2019 – with the aim of addressing the then diagnosed Currency, Debt and Growth (CDG) crisis – the major drives of inflation have been, among others;

- exchange rate depreciation – given that most domestic prices are largely indexed to the United States Dollar,

- adverse expectations – especially in the period up to the introduction of the foreign currency auction system in June 2020,

- adjustments to administered prices, including utility charges such as water and electricity tariffs, as well as the monthly adjustments to fuel prices,

- money supply growth, but with the bulk of the pass through or transmission happening indirectly via the exchange rate depreciation, and

- exogenous factors such as rise in oil prices on the international commodities markets and higher producer prices and logistical costs in South Africa, the country’s major trade gateway (not trade partner!).

These factors, together with the continued lack of balance of payments and budgetary support – a critical component in the quest to pursue the twin objectives of economic growth and stability – as well as observed experiences from countries such as Bolivia, Argentina and Liberia that have gone through similar reforms and transitions – will largely shape the scenarios.

In the interest of time and space, I will end here for now. The next article will expand on the inflation scenarios for the rest of 2021 and the year 2022.