Is Batoka good value in climate change?

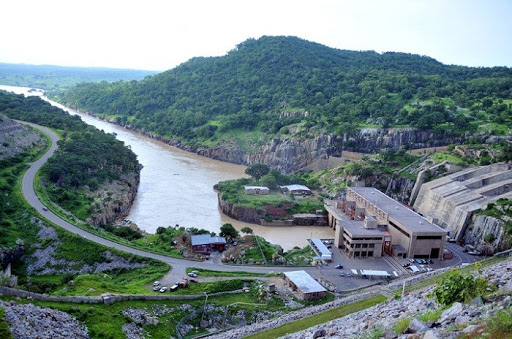

The very low rations of water for power generation at Lake Kariba now in force, just an average of 214 megawatts for each of the two power stations, suggests strongly that Zimbabwe and Zambia need to seriously rethink their strategic plan to build the Batoka scheme between the Victoria Falls and Kariba.

It might well result in some of the most expensive power in Africa if the output is well below the expectations based on the measured flows since 1925 over the Victoria Falls, the only real inflow into the scheme, minus perhaps up to 20 percent to account for climate change.

If the inflows are significantly below that 80 percent of average then the two countries might be building one of the larger white-elephants.

The Zambezi River Authority, which has been overseeing the planning of this hydro-scheme for more than 35 years, has given an estimate of a little over US$3,6 billion for the capital costs, including the interest payments, for the uS$2,1 billion dam wall and the two power stations each costed at US$732 000.

While everyone talks about a pair of 1 200MW power stations, one on each side, the detailed studies have never suggested that Batoka will be producing anything like this for most of the year. Lake Batoka will be a long thin lake with a far smaller energy storage than Lake Kariba.

The Zambezi River has a highly fluctuating monthly flow, ranging on historical averages from 262 cubic metres a second in October to 2 958 cubic metres a second in April as the annual floods reach their peak.

These are the averages from 1925, when accurate measurements of flows over the Victoria Falls started, to 2014.

Even those averages vary considerably when decade-long averages are taken into account. For example during much of the 1960s and 1970s flows into Lake Kariba were well above historical averages, so much so that British consultants were recommending very strongly a significant expansion of the two Kariba power stations.

At this time, even after Kariba North at around 600MW was commissioned to join Kariba South’s then 660MW, before a rebuild of the outraces under a new design increased efficiency to 750MW without using more water, floodgates had to be opened at times. Neither power station was ever rationed to operate below maximum output.

This meant that Capco, the then dam owner and operator and also the operator of Kariba South, never had to reduce sales into UDI Rhodesia even after taking into account the Zambian generation requirements. Kariba North was owned and managed by Zesco, although Capco had some unofficial oversight.

That made the political situation a lot easier as well. The complications of trying to organise generation cuts at both power stations during the very difficult Zambia-Rhodesia relations during UDI would have been horrendous, with the Rhodesians being particularly difficult.

During the 1980s Zimbabwe had a small but highly competent group of engineers working in the then Ministry that oversaw energy.

This group was not desperately enamoured over external consultants from Britain, certainly not seeing them as the supreme all-knowing external group, and checked the figures.

By this stage average annual inflows had decreased from that 15-year high and were now close to the longer-term annual inflows since 1925.

The Zimbabwean group were dubious about the wisdom of the huge investment required to expand the two power stations and pressed very hard for the second phase of Hwange Thermal instead, adding the 440MW of that phase to the 480MW already commissioned or in the process of being commissioned at Hwange phase one, largely using the civil engineering done by the UDI regime in the 1970s when work suddenly came to a halt after a sanctions-busting deal was exposed and the mechanical and electrical components were blocked.

Eventually, in the 2010s, the two extensions at Kariba did go through, starting with the north bank. At this stage both Zesa and Zesco recognised that the extensions would not add more energy to the Kariba output, but that they would allow the two utilities to cope with the huge hourly fluctuations in demand during a day.

Both now had good power stations to provide far more of the base load, Zesco with its pair of dams and power stations on the Kafue recently upgraded, and Zesa with Hwange Thermal that admittedly needing some maintenance catch up.

Both could then use their Kariba stations as a hydro should be used, to cope with the hourly fluctuations between say 2am, when just one or two generators would be in use at each station, to 7am or 5pm when both went through major peaks as miners, industrialists and domestic users were all going flat out.

The lower flows in recent years into the lake have meant that these two extension have never really pulled their weight, so the costs have never really been justified.

The other ground for the extensions were to be ready for Batoka, which without the huge storage of Lake Kariba, would have to vary output considerably.

The Zambezi River Authority, looking at the energy output, had predicted an average variation between 4 282 gigawatt hours in the second quarter of each year, as the two stations averaged just under 1000MW each, down to 872GWh in the fourth quarter, as they averaged just over 400MW each, about a sixth of their maximum. The monthly variation in inflows really hits that scheme.

Batoka and Kariba would have to be run as a pair. During the annual floods the two Batoka stations could be taken right up to averaging over 80 percent of their maximum of 1200MW each, while the Kariba stations would be cut back and let the flood waters coming through the Batoka stations fill the lake.

By the fourth quarter, when the Batoka stations were cut right back the extended Kariba stations would be going flat out.

So while there was talk about an extra 1 200MW on each side, the actual extra would be around half that. This is the problem of having the main storage dam downstream of the floodwater power stations. These days even that extra average 600MW might be a gross overestimate.

The present flows seem to be less than predicted. More than 80 percent of the Victoria Falls flow comes from Angola and the rest from western Zambia.

Zimbabwe’s contribution is trivial until you reach the Manyame and Mazowe confluences, which help Cabora Bassa but not dams Zimbabwe can use, and the main central Zambian runoff goes into the Kafue which enters the Zambezi well downstream of Kariba.

Even the 2022-s023 season, which was counted above average, saw the Angolan flows down as a semi-drought hit the main part of the upper catchment.

Zimbabwean experts had pressed hard in the 1980s for Mupata Gorge, downstream of Kariba and the Kafue dams, so it would in effect have a regular daily flow with almost zero fluctuation, simply reusing the water that had already generated power.

This was killed by a huge environmentalist campaign over the Mana Pools being flooded, and by the time the engineers had modified their proposal for a lower dam at Mupata using different types of turbine that worked on concentrating river flow more than on creating a long drop, it was too late. Mupata was killed.

But that low level scheme for Mupata now seems to be a better option. Detailed work would have to be done, but the huge advantage in a starting point would be the regular daily flow from the Kariba and lower Kafue power stations, and the ability to use the huge storage of Lake Kariba.

At the very least there would be a predictable daily output and the low-wall would minimise environmental impact since storage would not be required at Mupata, just the drop.

All this means that the power stations would be a lot cheaper than Batoka since there would be no need for extra to cope with the floods before cutting back; just enough to recycle Kariba and Kafue water.

No one since the original Zimbabwean 1980s estimates has calculated costs of construction and the eventual cost of power from the scheme, and those original estimates were not detailed.

So detailed costs would now have to be done. At the very least we could then do the power costs assuming say three quarters and even half flows in the Zambezi from Angola and Zambia.

There would be need for a new environmental impact study, this time with the low wall option on the table, but the impact would now take into account the global warming requirements and the fact that other options for Zambia and Zimbabwe involve coal and gas, carbon fuels.

Whatever solution is used, there will be an environmental impact, the trick would be to find the lowest impact for the most guaranteed power, the stress being on that concept of guaranteed.

Just because Batoka was the best 1990s scheme does not make it the best 2020s and 2030s scheme unless we are collecting white elephants.-ebusinessweekly