Zim’s critical minerals law favours China

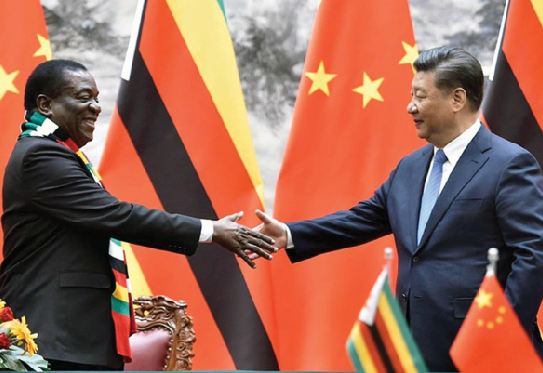

The world’s clean-energy transition will be impossible without African minerals — and a degree of resource nationalism from African countries is benefiting China, which has for decades invested in the African green-energy market and accounts for 59 percent of the world’s lithium refining.

Chinese companies run the majority of Zimbabwe’s mines and are better positioned to expand domestic processing there.

Lithium, often referred to as “white gold” is essential to producing solar panels and the rechargeable batteries that power electric vehicles; and in 2022, demand pushed prices up by more than 100 percent.

Africa could supply a fifth of the world’s lithium needs by 2030, but to best serve citizens, African leaders are demanding that miners go beyond extraction and add value by locally processing the raw mineral.

Last December, Zimbabwe, which has Africa’s largest lithium reserves, imposed a ban on raw lithium ore exports, requiring companies to set up plants in the country and process ore into concentrates before export in order to boost local jobs and revenue.

Those seeking to export and not process domestically would need to provide proof of exceptional circumstances and receive written permission to export raw lithium ore.

Zimbabwe’s ban, called the Base Minerals Export Control Act, will stop the country losing billions in mineral proceeds to foreign companies, officials said.

Namibia has followed suit; and in 2020 around 42 percent of African nations, excluding those in North Africa, had implemented restrictions on raw exports, including the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, and Nigeria.

Traditionally, “mining companies after extraction enjoy all the benefits (while) leaving communities in their catchment areas to bear the brunt of life-threatening dangers associated with their operations,” Edmond Kombat, research and finance director of Ghana’s Institute for Energy Security, told ESI Africa.

“It is time to stop that practice.”

However, China, which controls the world’s critical minerals supply chain, is ideally placed to reap benefits in these situations, because several Chinese owned companies have recently completed processing plants in the country.

Chinese-owned companies have spent more than US$1 billion acquiring and developing lithium projects in Zimbabwe, which in contrast has seen very little Western investment.

Last month, Chinese minerals giant Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt opened a US$300 million lithium processing plant at its Arcadia mine in Zimbabwe, which it bought last year from Australia-based Prospect Resources for US$422 million.

The plant currently has the capacity to process around 450 000 tonnes of lithium concentrate annually. Under Zimbabwean law the refined lithium can then be exported for further processing into battery-grade lithium outside Zimbabwe.

In May, another Chinese company, Chengxin Lithium Group, commissioned a lithium concentrator to produce 300 000 tonnes per year at the Sabi Star mine in eastern Zimbabwe.

And China’s Sinomine Resource Group said last month it had completed a US$300 million lithium plant, after it bought Bikita Minerals, one of Africa’s oldest lithium mines, for US$180 million.

Zimbabwe hopes to satisfy 20 percent of the world’s total lithium demand when it fully exploits its known lithium resources.

“If we continue exporting raw lithium we will go nowhere,” Deputy Mines Minister Polite Kambamura told Bloomberg last year.

“We want to see lithium batteries being developed in the country.”

New rules stipulate that a 5 percent royalty rate will be payable on lithium exported, due half in cash and half in processed final products so that the country can build cash reserves it could use for government-backed borrowing.

US sanctions on Zimbabwe, imposed since 2001, have impacted the country’s access to borrowing and investment, leaving few options but China.

Last year, Zimbabwean Finance and Economic Development Minister Mthuli Ncube claimed the country has lost more than US$42 billion in revenue as a result of Western sanctions.

The Zimbabwe Investment Development Agency reportedly received 160 lithium investment applications from investors based in China in the first half of 2023 compared to just five from the United States.

Even among Zimbabwe’s regional peers, US companies have been left on the backfoot. Nigeria rejected Elon Musk’s Tesla in favour of Beijing-based Ming Xin Mineral Separation to build Nigeria’s first lithium processing plant in Kaduna state, in the country’s northwest region.

Nigerian officials reportedly rejected Tesla’s proposal because it did not align with the country’s new policies.

“Our new mining policy demands that you add some value to raw mineral ores, including lithium, before you export,” Ayodeji Adeyemi, special assistant to Nigeria’s mines and steel development minister, told Rest of World.

For decades, African economists complained that foreign companies extracted minerals without benefit to citizens. In 2015, Zimbabwean researchers estimated the country had lost US$12 billion due to illegal trade involving multinational companies in China, Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom — enough money to pay off Zimbabwe’s foreign debt.

Africa holds more than 40 percent of global reserves of key minerals for batteries and hydrogen technologies. Yet it’s predicted that, by 2030, more than 80 percent of the world’s poor will live in Africa, and about 75 percent of them in resource-rich countries.

It makes sense for African nations to step up efforts to increase quality jobs.

“The United States and Europe must ensure that the partnerships they are building in Africa are mutually beneficial and non-extractive,” Theophile Pouget-Abadie and Rachel Rizzo recently wrote in Foreign Policy.

“Otherwise, they will run headlong into the walls erected by an increasingly dominant Beijing.”

Washington in January signed a memorandum of understanding to help the Democratic Republic of Congo and Zambia develop an electric battery supply chain.

But China is going beyond this in terms of thinking about what African nations need. Beijing, for example, with support from the United Nations Development Program, is facilitating a joint research centre in Ethiopia to fast-track access to renewable energy in the country.

Experts warn that more African countries banning critical raw minerals exports will impede global decarbonisation. Zimbabwe’s ban is perceived as unrealistic because the country lacks skilled workers.

Some countries (Kenya, Tanzania, and Zambia) have implemented policies requiring mining companies to train locals, according to a recent World Bank report.

The report suggests national export bans alone can make countries worse off because investors simply move their business elsewhere, but that training requirements could ensure retention of investment and the creation of a skilled workforce. — Foreign Policy